How Colour Becomes Sound

Harmony, Structure, and the Logic Behind Drawing Music

At the heart of my practice, Drawing Music, is a simple but enduring question:

What happens when music is allowed to exist in space rather than time?

Music unfolds moment by moment, while drawing exists all at once. My work explores the meeting point between these two languages by translating musical scores directly into colour — not as illustration, but as a parallel system shaped by structure, relationship, and progression.

The idea that sound and colour might share underlying principles has long fascinated artists and thinkers. Isaac Newton explored parallels between the musical scale and the colour spectrum, while composers such as Alexander Scriabin associated musical keys with colour and imagined performances combining sound and light. My own work does not seek to replicate these systems, but it sits in conversation with them - rooted in the same curiosity about harmony across sensory languages.

How I Choose My Colours

When people ask how I choose the colours in my work, I often begin by saying that I work with the colours of the rainbow. It’s a simple phrase, but a deliberate one. It immediately evokes an ordered sequence - a spectrum in which colours exist in relationship to one another rather than as isolated events.

From the very beginning, what mattered most to me was how colours lead into one another. Red moves naturally into orange; orange into yellow; yellow into green. These transitions feel harmonious because they evolve gradually. A jump from red directly to green introduces a much sharper visual tension - a different kind of relationship altogether.

This sense of continuity became fundamental to my colour system. I wanted colour to behave as notes do within music: understood through proximity, progression, and flow. Harmony, in this sense, is not imposed, but allowed to emerge.

Numbers, Patterns, and Early Conditioning

Looking back, I can see that my attraction to systems, sequences, and coded structures began much earlier than my formal training in either art or music.

As a child, I loved activity books that resembled word searches - except the “words” were not words at all, but numbers. Simple groupings at first, combinations of two or three, gradually increasing in complexity to strings of seven, eight, or nine. I was fascinated by scanning the page, recognising patterns, and finding order within what initially appeared abstract.

In many ways, selecting colour today through strings of numbers and letters feels like a continuation of that early fascination. Referencing a precise colour code, for example e30613, is not a clinical or detached act for me, but a familiar and reassuring one. It allows colour to be understood relationally rather than symbolically, situated within a system rather than assigned a meaning.

I often think of this as a form of environmental conditioning: an early comfort with coded information, progression, and pattern recognition that now finds expression in my artistic process. Just as those childhood number searches rewarded patience and attentiveness, my work today relies on careful observation, and on how one element leads into the next, and how structure can quietly give rise to harmony.

It feels fitting that Drawing Music sits between music and colour - both languages shaped by sequence, relationship, and the unfolding of patterns over time.

The digital palette I work with

Working within a continuous colour spectrum allows for gradual, harmonious transitions. Individual colours are selected precisely using digital colour codes.

Tonal and Atonal: Seen as Well as Heard

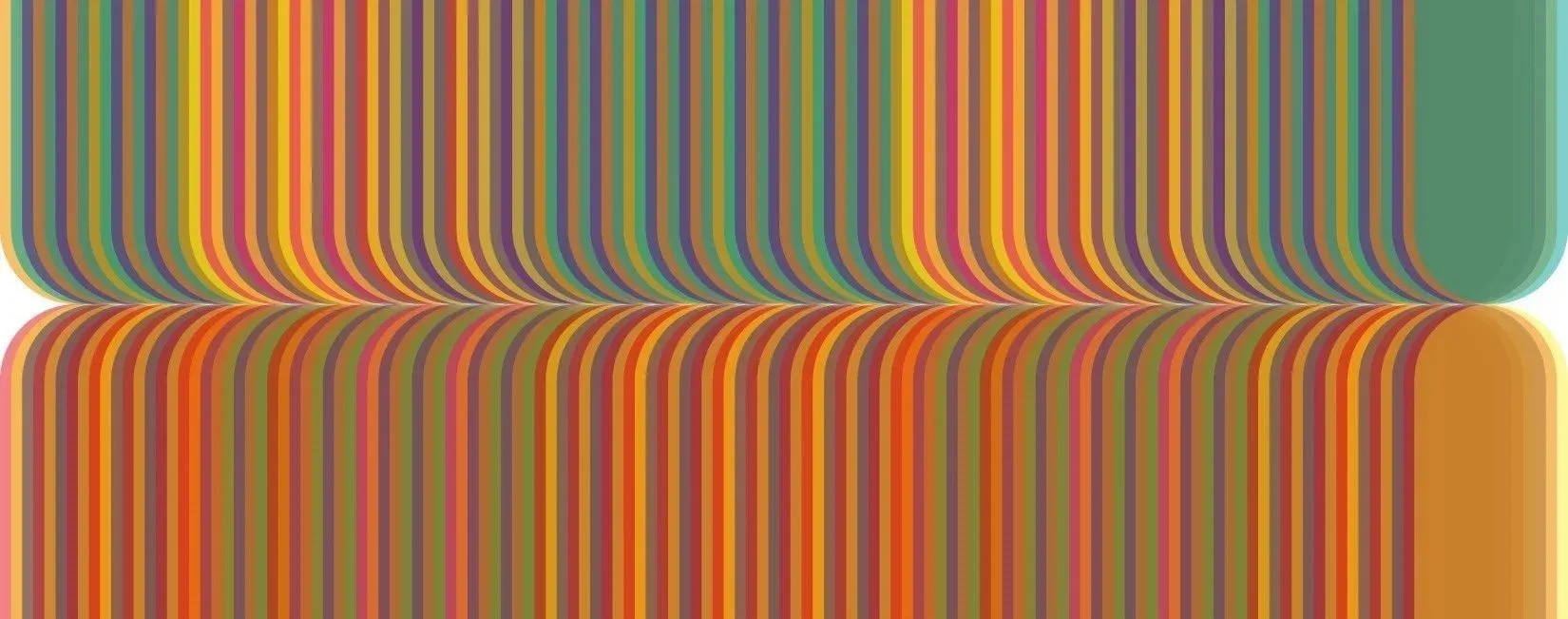

These ideas become particularly visible when comparing tonal and atonal interpretations of the same piece of music.

Top image: Tonal version of Ave Maria, Bottom image: Atonal version of Ave Maria

In tonal translations, colour often reveals a clearer sense of tension and release. There is a visible rise and fall as colours shift and resolve, echoing the directional pull of tonal harmony.

In atonal interpretations, colour behaves differently. Progressions may feel more continuous and evenly distributed, with less emphasis on contrast or resolution. Rather than moving towards a centre, colours coexist within a more generalised field.

Although atonal music can sometimes sound unfamiliar, its visual translation is not discordant. It simply carries a different flavour - cohesive, rich, and quietly harmonious in its own way.

Because my work translates note relationships directly into colour relationships, emotional qualities emerge through structure rather than being imposed. Just as music can be harmonious in more than one way, colour, too, can hold balance and beauty across different systems.

Music is usually something we hear and then lose.

Drawing allows it to remain - suspended in colour, structure, and space.