Why I Draw Music

On translation, colour, and letting music speak visually

For a long time, I’ve felt the need to explain what I do — not defensively, but honestly. To put language around a practice that lives between sound and colour, between listening and looking. This feels like the right place to begin.

Recently, I was listening to a podcast by Michelle Lynne, where she was speaking with guest, Dustin Boyer, about branding in the Classical music world. One point in particular stayed with me: within the classical repertoire, so many musicians are working with the same scores, again and again. What we hear is often less about asserting individuality for its own sake, and more about serving the composer — about conveying what the music itself is asking to express.

That idea resonated deeply with my own practice.

From performance to study

Music has been part of my life from a young age, and the piano was my first serious creative language. I completed all my piano grades and a Trinity Performance Certificate, and for a long time I imagined music might become my primary path. While I don’t claim the life or discipline of a professional concert pianist (and I still feel a genuine humility in the presence of those who have pursued music at that level) the way I listen has been shaped by years of study, practice, and attention.

There is also something more personal at play. When I was learning the piano, I was always aware that I didn’t spend enough time away from the instrument, studying the score quietly — sitting with the music, understanding its structure and inner logic beyond the demands of performance. Drawing Music has become a way of returning to the score away from the piano, engaging with the music as a visual artist….studying its structure, relationships, and logic through colour rather than through performance.

Translation, not performance

In Classical music, the performer is alive, present, and bringing something of themselves in that moment. Some composers, like Glenn Gould for example, have placed particular emphasis on the individuality of the performer and the act of interpretation itself.

My role, however, is different.

I am not performing the music. I am translating it.

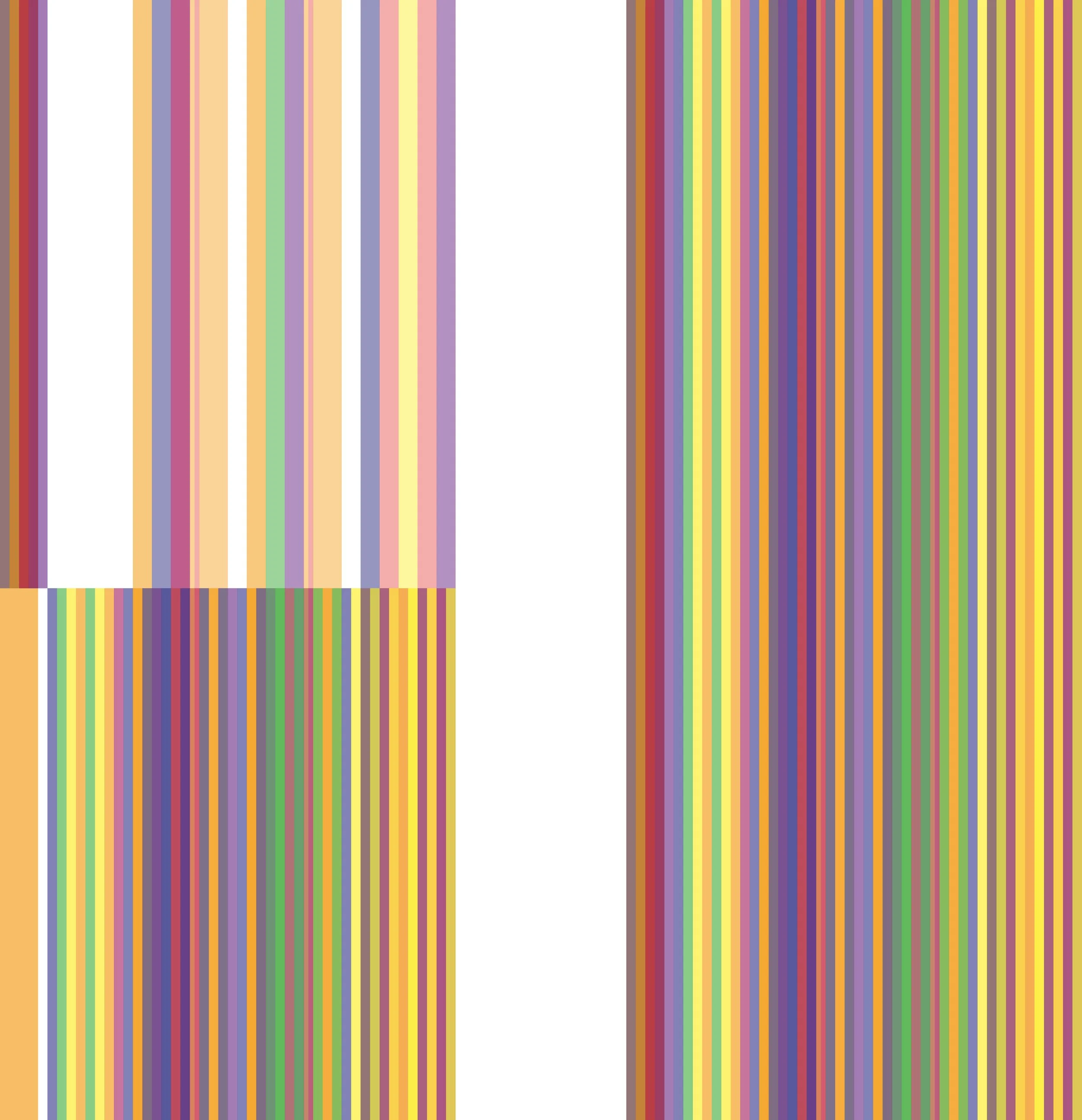

Working directly from the score, I translate musical notes into colour through a pre-determined system. Because of this, I am not expressing emotion through gesture or physical interpretation. Instead, I allow the music’s own truth and beauty to emerge visually, through the relationships between colours.

The emotional content doesn’t disappear — it simply shifts location.

Where the dynamics live

In my work, dynamics arise through colour itself.

Just as dynamics in music are created through contrast, tension, and resolution, the same happens visually. A red next to a blue creates one kind of tension. Red layered over green and pink produces another. How colours sit beside one another, how they merge, clash, or soften — that is where movement lives in my work.

This is why my process can appear methodical, repetitive, even dogged at times. I return to the same system again and again, much like the Classical repertoire returns to the same scores. But within that repetition, subtle differences matter enormously.

I am operating entirely within the visual field, yet the logic remains musical.

From Prelude in D Minor, Bach. Left: bars 5-8 separating right and left hand. Right: Bars 5-8 blending left and right hand

Digital drawing, light, and material

There is often an assumption that digital work is easier, quicker, or emotionally thinner than traditional drawing. I’ve wrestled with that idea myself. But for me, working digitally allows me to mix colour through light rather than pigment — and colour, quite literally, is light.

Digital colour is governed by coded systems, numbers, and relationships (not unlike music notation itself). Every decision is intentional. Every mark is chosen.

My top-of-the-range works are printed on ChromaLuxe aluminium panels using a sublimation process that permanently fuses colour into metal, creating exceptional depth and luminosity. Alongside these, I also produce limited edition prints on fine art paper. These are equally carefully considered, signed, and editioned works that offer a different, more intimate way of living with the work. Metal amplifies light and saturation, while paper offers softness and quiet presence. Both are integral to my practice.

Why I’m sharing this

I’m writing this because connection matters.

Drawing Music is not about decoration. It is about attention. About listening carefully, translating faithfully, and trusting colour to carry what sound has already communicated.

This year, I’ve committed to writing one blog post each month. This will be a space to share not just finished work, but the thinking, listening, and quiet processes behind it.

If my work resonates with you, it’s likely because you recognise that space too — where meaning builds slowly, and repetition becomes devotion.

That is where my work lives.